What war directly led to the 13th amendment?

We're learning a lot these days nigh the historical roots of mass incarceration. Michelle Alexander's wildly successful book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness now has a cinematic companion, Ava DuVernay's documentary "13TH." The moving-picture show's powerful overview of the crisis of mass incarceration from the Civil State of war to the present has earned it plaudits from critics, activists, and scholars. But we need to revisit its faulty foundational history.

DuVernay'south championship refers to the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery throughout the state when it was ratified in 1865. In the documentary, Jelani Cobb argues that the amendment created a "loophole" that permitted the massive criminalization of blackness that has divers the mail-emancipation experience from Jim Crow to the prison house industrial complex.

The disquisitional text reads:

"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a penalization for crime whereof the political party shall have been duly convicted , shall exist inside the United States, or whatsoever place subject field to their jurisdiction."

The film argues that the fundamental dependent clause of this commodity is the trouble. The country prohibited people from being deprived of their liberty, merely with a critical exception: they could at present be imprisoned, whether on chain gangs or in modernistic penitentiaries. Equally the picture show'southward intertitles state, the African American went "from slave to criminal with one amendment."

Many accept adopted and extended this argument. One author commenting on the documentary calls the exception clause "a poison pill, a trapdoor, an escape clause" that permitted the persistence of slavery. He quotes another: "The 13th Amendment says slavery is still legal. Slavery is legal in prisons. Y'all better wake up and see this conspiracy for what it actually is." Some other claims, "in 2015, the 2 million (largely Blackness) people incarcerated in America are legally considered slaves nether the Constitution."

All of these have consequences. There is a Change.org petition to "shut the 13thursday Subpoena Slavery loophole." In states whose constitutions echo the linguistic communication of the amendment, like Wisconsin, efforts are afoot to strike the language. In Colorado, a ballot initiative to practice this recently failed.

In a nutshell, the statement is this: The country did the right matter in passing an subpoena intended to make all people equal, but some connived against that noble aim in permitting, and and so exploiting, the mass incarceration loophole. When we put these claims to the test with a closer await at the Subpoena and its origins, we learn that they carry piddling resemblance to the bodily history.

Outset, the "loophole" argument imputes to its framers and judicial interpreters a conspiracy against intentions of total equality that the subpoena never included in the first identify. All the Thirteenth Amendment did was abolish slavery; it stood virtually moot on the significant of freedom. This was by design. Antislavery legislators wanted a more comprehensive measure, but only by compromising on its vision would more bourgeois legislators let information technology pass. It took afterward amendments and laws to define freedom: the Ceremonious Rights Human activity of 1866 (civil rights), the Fourteenth Amendment of 1868 (citizenship), the Fifteenth Amendment of 1870 (voting rights), and others.

Second, on its face, the linguistic communication of the Thirteenth Subpoena'southward "exception clause" offers no mechanism to actively promote incarceration. Instead, its obvious purpose is to ensure that none mistake the prohibition on racial slavery for a prohibition on criminal incarceration. Given the novelty of emancipation at the phrase's origin, that was not pointless: surely the abolition of slavery should not mean that no one (black or white) could always exist incarcerated for crimes they committed, correct?

The exception clause lonely did cipher to promote racial oppression. Search in vain for legal cases in which the clause was used to contend for the legality of whatever grade of punishment. Instead, nosotros meet the opposite, as in in U.S. five. Ah Sou, C.C.A.9 (1905), wherein the court used the clause to argue confronting deporting a Chinese woman because it would have returned her to a state slavery in China. To justify their oppression, white supremacists used much more powerful and overt legal devices than glace language in the Thirteenth Amendment. Jim Crow and mass incarceration would've happened with or without the exception clause.

The clause itself elicited little word in 1865, largely because it was not new at all. We easily forget that by end of the Civil War the United States had already experienced the abolition of slavery in northern states. Vermont had written slavery out of its country constitution in 1777; Massachusetts abolished it through judicial rulings in the 1780s. States such as Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey passed gradual emancipation laws that phased it out over time.

When the country expanded into the Northwest Territory in 1787, the very twelvemonth delegates met to devise a new constitution, Congress decided that slavery would be prohibited in the new lands. Compare the slavery prohibition of the linguistic communication of the Northwest Ordinance with that of the Thirteenth Subpoena:

1787: "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall take been duly bedevilled."

1865: "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except equally a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall be within the United states of america, or any identify subject to their jurisdiction."

Everyone in 1865 openly acknowledged and discussed this debt to the Ordinance of 1787. They were not the get-go. The linguistic communication of the Ordinance echoed in the constitutions of every country carved out of information technology (see Minnesota'due south here), as well as many far western states. The exception clause had long served the purpose it served in 1865 and 1787—to distinguish, not merge, slavery and criminal incarceration.

Past 1865, the exception clause had go boilerplate. Information technology drew attention just from Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who objected to it precisely considering it created defoliation. While in 1787 there may take been need to distinguish between slavery and penal servitude, Sumner argued, "that reason no longer exists." The clause should be excised, he urged, because it had become pointless: "'imprisonment' cannot exist confounded with this 'peculiar' wrong," he stated, referring to the "peculiar" (i.e., specifically southern) institution of slavery. Following Sumner'south communication and leaving the exception clause out of the Thirteenth Amendment would have certainly obviated our present defoliation over its meaning. But since unlike means were used to implement Jim Crow and mass incarceration, they would've happened anyway.

The Thirteenth Amendment did goose egg to promote mass incarceration in freedom, simply neither did it practice anything to limit abuses of the criminal justice arrangement that stopped curt of bodily slavery. The law had long distinguished between slavery and incarceration, and no one intended the Thirteenth to erase that distinction. Its only intent had been to prohibit the holding of people every bit property. When civil rights advocates in the 1870s began arguing that discriminatory laws conferred a "badge of servitude" on blacks, they were roundly rebuffed because the measures were race-neutral on their face up.

Upon emancipation, the freedpeople chop-chop learned that this was a stardom without a divergence. This is what people mean when they merits that emancipation "didn't matter."

Only it did. Mass incarceration was the product not of slavery just of freedom—of a liberal social club premised on individual rights of belongings, especially in self-ownership. Liberal legal regimes had destroyed slavery by defining it equally a barbarian rejection of the modern, but to then promote forms of mass incarceration as legitimate if unfortunate necessities of life in "liberty."

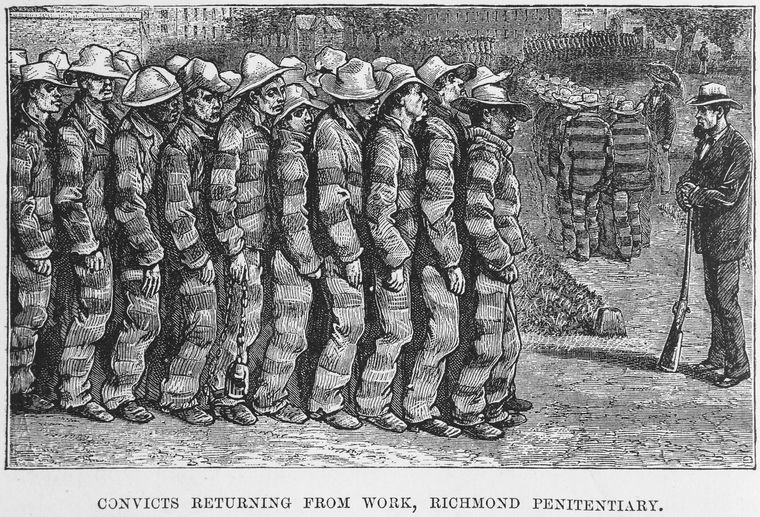

"13TH" makes the laudable instance that racially-specific, for-turn a profit exploitation of a criminalized underclass should be no more legitimate than was slavery. Just in mischaracterizing the function of the Thirteenth Amendment it underplays the depth of the trouble in both history and the nowadays. There was no need for hugger-mugger linguistic communication or tricky loopholes. Southern state governments worked openly to pass the legal mechanisms that criminalized blackness and poverty, from blackness codes and apprenticeships laws to vagrancy provisions and convict charter systems. The culprit was non the persistence of an old and rejected labor authorities, merely the emergence of new ones, which the land constitute much easier to justify.

Slavery and mass incarceration are not the same. All forms of racial oppression are not forms of slavery; rather, slavery is one form of racial oppression. Mass incarceration is another. While it may help to stop it by associating it with an establishment we abolished, it is not the remnant of a barbaric and outmoded organisation only the product of modern society. The trouble isn't the persistence of slavery; the problem is how a system that has always promised justice for all always seems to observe ways to deny it to some.

If nosotros can only see ongoing racial oppression equally a remnant of slavery, then we can't run across it as a problem of our ain historic period. And if we tin't understand mass incarceration as a problem of our own age, we can't critique the mechanisms that foster racial and economical inequality in a organisation that is supposed to be blind to both.

But just as it became possible to topple a world in which slavery was an unquestionable norm, and so also information technology can become possible to topple a world in which mass incarceration and other systematic forms of inequality are an unquestioned norm. We demand simply call up such a world into existence.

Patrick Raelis Professor of History at Bowdoin Higher. He is the author of numerous essays and books, including Black Identity and Black Protest in the Antebellum North(N Carolina, 2002), and his nigh recent book, Fourscore-Viii Years: The Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777-1865 (Academy of Georgia Press, 2015).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not exist reprinted without permission.

Source: https://www.aaihs.org/demystifying-the-13th-amendment-and-its-impact-on-mass-incarceration/

0 Response to "What war directly led to the 13th amendment?"

Post a Comment